Once we have created a satisfactory cause and effect diagram we can use it to inform choices about improvement. There are a number of principles to bear in mind.

First we must address root causes. We have already understood the concept of cause and effect driver trees. At the very tips of the branches we find the core enablers – the building blocks that drive everything else. So for example in figure 8 there is only one root cause, “target performance”. Root causes can be far removed from the results we are trying to influence. If we choose to ignore root causes any results we do achieve will be illusory and unsustainable.

It can be very tempting to take the easy route with a quick fix. For example, a tight flash noseband will ensure our horse doesn’t open his mouth because he can’t! This is an easy quick fix in that it treats the symptom but it doesn’t treat the cause. Ask yourself, why is the horse opening his mouth in the first place? If it is because of an uncomfortable bit or a problem with his teeth or a rider’s insensitive hands the quick fix may mask the symptoms in the short term. In the long term the real cause will wreak havoc elsewhere.

Can you think of any other obvious quick fixes that fail in horsemanship?

Some fixes become addictive. A good example of this is fiddling the horse’s head down. This results in a change in the outline but without acceptance in the horse. The minute the rider stops fiddling or holding the horse’s head down then the problem immediately resurfaces and so we have to do it more – more fiddling and therefore more strength needed by the rider. The horse’s head waggles from side to side or he over-bends; we simply shift the problem elsewhere.

Sometimes we unintentionally escalate a problem and make it far worse than it would otherwise be. I discovered that my Lusitano, Eric, does not like to work in the rain or indeed in a school with surface water splashing on his nose. Of course I can avoid riding outdoors in the rain or ride indoors but sometimes this is not possible. If, as I come towards a puddle, I react by tensing in the expectation of a fight, invariably the fight happens. If, on the other hand, I focus on doing nothing and inhibiting my reaction then there is no fight. He reacts to the puddle but I don’t react to him and therefore escalate the problem.

We can react or we can pause to think and choose a different way. It is up to us.

Can you think of any instances where you have reinforced bad behaviours in your horse?

Second, we can only take action within our sphere of influence. Some enablers will be within our influence and others will not. Any intervention must be designed around those enablers that are within our sphere of influence. It is pointless and frustrating to try to influence things that are outside our control.

The thing we are most able to change (as it is directly in our sphere of influence) is our own behaviour.

Third, we must understand the role of time. How long will it take to change an individual variable? And what about timing? Is there a better or worse time to take action?

Some variables may be changed quite quickly. Others may take a lifetime to change. Usually our ability to influence things increases as we extend the time horizon we consider. When we consider “forever” (infinity), anything is possible. This means that what we can work on in our next hour is necessarily limited. And our focus must always be on the core enablers.

Fourth, we must identify and remove blockers. It is pointless pushing on the accelerator with the brakes firmly on. How many times do we see riders complaining about their horse’s lack of energy but they are riding with a very strong contact?

Fifth, look for leverage. That is the little intervention that makes the big difference. Feedback loops give us leverage. Once we engage a reinforcing loop in a virtuous direction we will continue to reap great benefit…until something changes. We are constantly seeking leverage when we ride our horse. In this instance, leverage is his sensitivity to our requests. We need to find out how little we can do to get a response in the right direction and then aim for less……

To find out “how little” we must be prepared to experiment. And we must be able to start from a position where we are sure we are doing nothing to start with (ie our effect on the total system is passive).

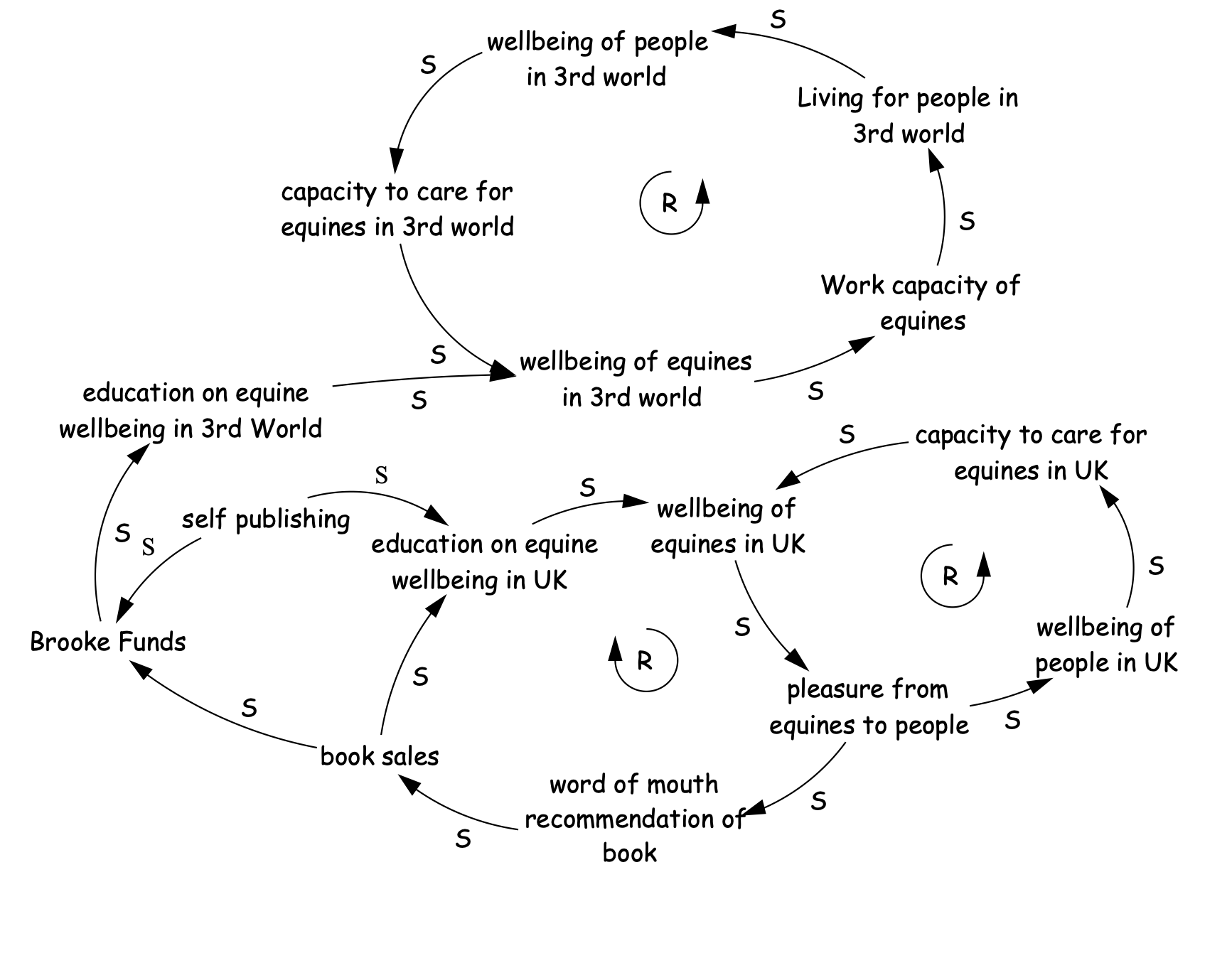

Finally remember that for an action to succeed we must know what to do, how to do it, and why to do it. The existence of this book is a testament to this approach. Consider the following diagram. Have a go at understanding it!

Figure 10 Impact of this book

The diagram captures the cause and effect logic for the existence of the book. You may remember the following words from chapter 1:

“I also wanted to give something back. To whom? To horses and their people. I feel that by sharing this thinking with people like you in the developed world I hope that I can benefit people and horses in the developed world. Equally, by using the book to raise funds for an international horse charity, The Brooke Organisation, I am benefiting equines in less developed countries and therefore the people there who depend on them for their livelihood. And by buying this book you are too.”

For more information on Systems Thinking see Peter Senge’s “The Fifth Discipline” (26) and Dennis Sherwood’s “Seeing the Forest for the Trees” (27). Further resources can be obtained via Pegasus Communications (39).

Things to remember

To achieve a harmonious equilibrium with our horse we must understand the structure of the system.

Structure affects behaviour.

Mental models can be made explicit by using the language of Systems Thinking.

There are only two types of relationships between variables: Supporting and Opposing.

There are only two types of feedback loop: Reinforcing and Balancing.

Reinforcing loops are very powerful and can be vicious or virtuous in their impact.

Driver trees are a linear way of looking at a causal loop diagram.

Equilibrium is a state without change.

We can use Systems Thinking to think through the consequences of our actions and so make better informed choices.